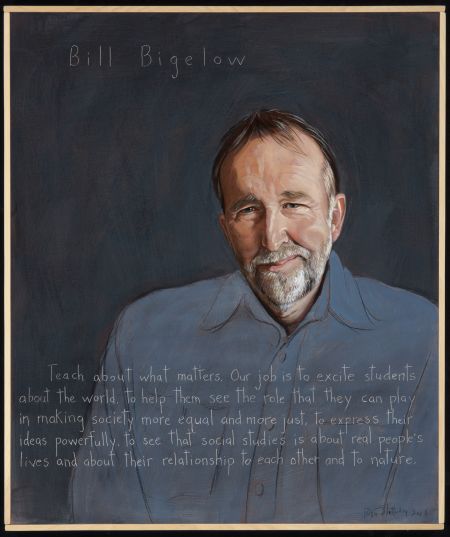

Since for the last two months we focused a lot on education and climate justice, we also explore the world outside of the IYNF and our training. We talked to Bill Bigelow, a co-director of the Zinn Education Project, which is most likely the most comprehensive site for climate justice education resources in the United States.

What should people know about the Zinn Education Project?

The Zinn Education Project is a collaboration between Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change that began in 2008. The project takes its name from the great U.S. historian and activist Howard Zinn, who wrote A People’s History of the United States, which is the best, most honest overview of U.S. history and has sold millions of copies. Our aim in the Zinn Education Project is to provide educators with “people’s history” teaching materials to teach more critically and honestly about the world. Too much history teaching looks at the world from the standpoint of history’s winners — the rich, the elites, the presidents, the generals. Our aim is to look at the world from the standpoint of the people who are so often missing from the story: people who were enslaved, workers, women, Indigenous people. And to focus on movements for social change.

You provide teaching materials to educators. How does this cooperation work?

Yes, that’s our main aim: to provide free downloadable people’s history teaching materials to educators. We now have more than 120,000 people who have signed up at the Zinn Education Project to access our lessons. We also lead workshops for schools, school districts, and teacher unions, around the United States, and sometimes in Canada, too. With increased activism around climate justice and racial justice, we have more than twice as many people signing up to access our resources as this time last year. So that’s very hopeful. In October of 2020, 2,600 educators registered at ZEP. Teachers are hungry for materials that engage their students about issues that matter.

How is the Zinn Education Project addressing topics like climate change and climate justice education?Can you tell us more about the Teach Climate Justice campaign?

In 2007, I began work on a teaching book focused on climate justice with my colleague Tim Swinehart, A People’s Curriculum for the Earth. It was published in late 2014 by Rethinking Schools, where I am curriculum editor. We began the book because the mainstream curriculum was so terrible in its treatment of climate change, and teachers needed alternatives. The global studies textbook in Portland, where Tim and I live, included only three paragraphs on climate change, and one of the paragraphs began, “Not all scientists agree with the theory of the greenhouse effect.” So we wanted to collect lesson plans and readings that teachers could use to bring these issues to life with their students. Over the past couple of years, we have built a Teach Climate Justice site at the Zinn Education Project, and have posted lots of articles and lessons from Rethinking Schools publications. Our aim is to offer educators a place to find teaching resources that look at the roots of the climate crisis and that get students to come to see themselves as activists responding to the crisis. We think it’s the most comprehensive climate justice teaching site in the United States. Teachers can go there and be inspired by the stories of other teachers.

Can you think of any milestones that somehow really affected climate justice education in the past years?

In 2015, teachers, parents, students, and climate activists in Portland, Oregon, began meeting to write a climate justice policy that we hoped the local school board would pass. There are about 50,000 students in the school district. The following spring, in 2016, the school board passed the most comprehensive climate justice resolution in the country, which inspired similar efforts around the United States. What we have seen in Portland and elsewhere is that the more climate justice is a part of the curriculum, the more students want to become active in addressing it. Students in Portland demanded that the school district allow and even encourage student participation in the September 2019 strike for the climate — which they did. Not only did school administrators agree to treat student participation in the strike as an excused absence, they sent letters home to parents saying that although this was not an official school event that climate justice is part of the core curriculum and students’ participation in the strike should be considered part of their education. This was a huge victory, and climate activists and students even got the school district to agree to hire a full-time climate justice coordinator. The school district also supported students who attended a public rally for the Our Children’s Trust plaintiffs, who are suing the United States government for its policies that make the climate crisis worse.

If you could think of anything that could be improved in the American public education system when it came to climate change education, what would it be? What is the key struggle of the curriculum?

Great question. The key struggle is still to get school districts to acknowledge that there even is a climate crisis, and that addressing it needs to be a central component of the curriculum. One of the things we’ve noticed in the United States is that school districts try to put climate change entirely in the science curriculum. No doubt, it does belong in science, but it also belongs in social studies, because the roots of the crisis are social, they are economic. We have an economy that is laser focused on profits, and this has led to climate chaos. And just as the causes of the crisis are social, potential solutions are social. But climate also belongs in language arts classes, in mathematics, in health, in music, in agriculture. So that remains a challenge: making sure that climate change is taught throughout the curriculum, and in the youngest grades. And one other thing: The aim of teaching about the crisis should not be to scare young people. It should be to inspire them to think about how a “just transition” to a non-fossil fuel future can make the world healthier and more equal. Students need to know that there is important, joyful work in creating a new society to protect the climate — and each other.

What is different when it comes to young people now and for example 20 years ago? Are they keen to learn?

Well, I cannot speak for all young people, but it does seem that there is a much greater eagerness now to be part of social justice movements — and to do the kind of learning that will allow them to participate effectively. Look at how young people became active in the United States after the murder of George Floyd, in response to organizing to make Black Lives Matter. And last fall, millions of young people participated in the biggest climate strike in history — including the 20,000 that took to the streets in Portland, Oregon, one of the biggest demonstrations in Portland’s history. So despite the terrible crisis with COVID-19, and so much misery around the world, I think that the activism of young people makes this a hopeful time. And we defeated the horribly racist, xenophobic, misogynistic Donald Trump for president, so there is hope in that, too.

I know you spent many years working as a high school teacher. Did you also motivate your students to be more active in civic matters, activism?

I wanted my students to know that young people throughout history have participated in social movements. Whether we were studying the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa or the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee in the U.S. South in the 1960s, I showed my students young people who were making a difference in the world. Of course, it is inappropriate for teachers to recruit students for particular organizations, but it is appropriate — even essential — for teachers to emphasize in the curriculum that everything good and decent and democratic in our society is because people organized and fought for it. And that young people have played a vital role in those struggles. One piece of the Portland school board’s climate justice resolution says that “students should develop confidence and passion when it comes to making a positive difference in society, and come to see themselves as activists and leaders for social and environmental justice.” This should be every educator’s aim.

You are also a curriculum editor for Rethinking Schools magazine, you are the author of many educational books. What is your drive here? What is your favorite part about working with youth?

Yes, my work with Rethinking Schools and writing about teaching begins from my commitment to my students. I always have felt very at home with high school students, and young people in general. It’s been said before, but most young people have a keen sense of right and wrong. When they learn, for example, that some people are getting rich drilling for oil and gas, and mining coal, and that because of the increasing concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, other people around the world — mostly poor people — are suffering, young people recognize how profoundly unfair that is. How wrong it is. And they want to do something about it. It’s that heart of justice that is so much a part of youth that always motivated me as a teacher. Also, the teaching methods that I’ve developed are participatory, sometimes playful. My favorite part of teaching is watching students come to life in an activity, and knowing that this engagement is going to be the source of learning something important about the world.

Are you aware of any European equivalents of what you guys do with the Zinn Education Project?

I am not. However, recently I spoke at a conference organized by the National Education Union in Great Britain on “Climate Crisis and Education.” The teachers union there has a wonderful Climate Change Network, and being part of that gathering made me realize that we need to find more ways to share our experiences and to talk across borders, because the work we are doing with educators and with young people is so similar, and yet we so rarely share experiences with one another. There were primary school teachers who spoke during the event who are dealing with the exact same issues that primary teachers in the United States are dealing with. We need to be connected.

In Europe and the EU it is pretty common that we are able to organise many international activities (mostly thanks to EU funding) where people from like 20 different countries can meet and learn together and exchange their experiences. Is there anything like this happening in the US (e.g., exchange programs between schools from different states)?

Sponsored by the government? [Laughs.] No. Not the U.S. government. However, there are a number of important social justice conferences that give educators and young people a chance to come together to share experiences. The Teachers 4 Social Justice annual conference in San Francisco brings hundreds of people together every year. This teacher-led conference has been going on for 20 years. Our Northwest Teaching for Social Justice Conference that rotates every year between Seattle, Washington, and Portland, Oregon, is another. Chicago Teachers for Social Justice sponsors an annual curriculum fair, and once every two years Education for Liberation holds its “Free Minds, Free People” gathering, which includes lots of youth organizers, and people doing popular education, as well as teachers. Recently, the British Columbia Teachers Federation and the Surrey Teachers Association have sponsored a cross-border social justice education conference for Canadian and U.S. educators. It would be wonderful to have people in the United States as participants in European gatherings, and maybe now that so much of this work is online, we can do that.

Last, two questions, can you think of two books you would suggest to someone who wants to start and learn more about environmental and climate justice?

Well, at the risk of promoting my own book, I do think that our book A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis is the most useful book on teaching these issues. A book that remains an essential resource is Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. In Portland, we have a collective of teachers working to revise A People’s Curriculum for the Earth, and we found a Verso Press book, A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal, to be an inspiring and hopeful source of teaching ideas.

Any film suggestion regarding this matter?

Good question. There are a couple of short, animated films that we have used in our work here. A Message from the Future with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the new A Message from the Future II: The Years of Repair. Both of them imagine the transition to a just society, and how the movement for climate justice needs to be linked to broader movements for justice. They are illustrated beautifully and cleverly by Molly Crabapple. I also recommend the spoken-word performance videos by the Marshall Islands poet and activist Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner. We had the opportunity to work with Kathy in Portland for a couple of years when she was living here. Her poetry and videos should be part of every class or organization dealing with climate justice. See, for example, “Dear Matafele Peinam” and “Tell Them.” Kathy’s work deals with the climate threat to low-lying islands like the Marshall Islands, but also the lingering impact of nuclear testing, and Indigenous rights. Her work can spark excellent student writing.

Rise – a poem by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and Aka Niviâna

Rise: From One Island To Another from Mainspring Media on Vimeo.

Read the full poem, in different languages, as well as watch behind the scenes videos at the 350.org website.

Thank you for this interview!

Viktor Koren

Bill Bigelow is curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools magazine and co-director of the Zinn Education Project. He is the author or co-editor of many Rethinking Schools publications, including A People’s History for the Classroom, The Line Between Us: Teaching About the Border and Mexican Immigration, Rethinking Globalization: Teaching for Justice in an Unjust World, Rethinking Our Classrooms–Volumes 1 and 2, Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, and A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis. Bigelow lives in Portland, Oregon, and has taught high school social studies since 1978.

Pictures source © www.zinnedproject.org and © https://naomiklein.org/ ©Robert Shetterly/Americans Who Tell The Truth