By Max Menkenhagen

1895: The Birth of a Special kind of Organization

Depicting what the Naturefriends movement is about, where it comes from, and how it developed in the past 120 years is an interesting but difficult endeavor. If you ask ‘Who is this organization calling itself the Naturefriends?’ you might get a lot of different answers, depending on who you ask, when you ask, and how you ask. Typical answers include ‘A tourist club’, ‘a mountaineering organization’, ‘a cultural movement of the working class’, ‘a leisure organization with ecological consciousness’, or ‘a socio-environmental non-governmental organization that offers sportive and cultural leisure activities in nature and the facilitation of skills and opportunities needed for these’ (Schumacher, 2005). There is no one right answer because the Naturefriends have never been a homogenous group, nor have they remained the same since their founding in 1895. On an individual, local and even national level ideologies, political opinions, intentions and motivations, as well as the understanding of what the goal of Naturefriends activities should be, differ(ed) tremendously. For this reason, the depictions in this publication cannot be valid for the whole network and all of its members, even if its aim is to describe general trends of the movement at certain points of its history.

Depicting what the Naturefriends movement is about, where it comes from, and how it developed in the past 120 years is an interesting but difficult endeavor. If you ask ‘Who is this organization calling itself the Naturefriends?’ you might get a lot of different answers, depending on who you ask, when you ask, and how you ask. Typical answers include ‘A tourist club’, ‘a mountaineering organization’, ‘a cultural movement of the working class’, ‘a leisure organization with ecological consciousness’, or ‘a socio-environmental non-governmental organization that offers sportive and cultural leisure activities in nature and the facilitation of skills and opportunities needed for these’ (Schumacher, 2005). There is no one right answer because the Naturefriends have never been a homogenous group, nor have they remained the same since their founding in 1895. On an individual, local and even national level ideologies, political opinions, intentions and motivations, as well as the understanding of what the goal of Naturefriends activities should be, differ(ed) tremendously. For this reason, the depictions in this publication cannot be valid for the whole network and all of its members, even if its aim is to describe general trends of the movement at certain points of its history.

In 1895 the first Naturefriends organization was founded by social democrats in Vienna. Then called ‘Touristenverein die Naturfreunde’ (Tourist Club the Naturefriends, further referred to as TVdN), it was an organization for recreational and cultural activities of the working class. The small soon gained meaning within the international workers’ movement. In its early years the organization was dominated by trained craftsmen and apprentices. Supported by the magazine ‘Der Naturfreund’ found in the 1897, their then common Journeyman Years (the so-called ‘Waltz’) significantly helped to spread word about the young movement in the German-speaking part of Europe. Consequently, already in 1905, there were regional groups in Munich and Zurich. Austrian and German migrants even took the idea all the way over the Atlantic, establishing new Naturefriends communities in the Americas. Even though these could never reach the success of the movement in Europe, the organization was big enough to create a lively community praised for its ‘European atmosphere’ (expressed primarily through dancing the Schuhplatter, celebrating Oktoberfest, and drinking cold beer around a Maypole (See Gross, 2014, for more information about the history of American Naturefriends).

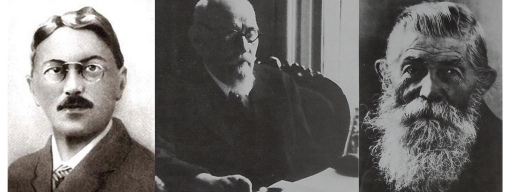

From the left side to the right: Georg Schmiedl, Karl Renner and Alois Rohrauer – the three main founders of the Naturefriends movement.

Merging environmental and social policy, the work of the TVdN originated in the aim to get workers out of the dark factories and small appartments, and into nature. Central political commitments were striving for peace, justice, and democracy, fighting against militarism and fascism, and improving living conditions of those members of society worst off. This included demands for lowering working hours, as well as the struggle for free access to natural areas. In this understanding the common greeting ‘Berg Heil’ (‘Mountain Whole’, loosely translated to ‘Good Climb’) used by the bourgeois majority of mountaineers was replaced by the revolutionary ‘Berg Frei’ (‘Mountain Free’), expressing the demand for free access to natural sites, which was rare back in the days because most trails were located on privately owned land and access was strictly limited. Naturefriends hikes into these areas turned into demonstration for free wayleave, possibly constituting the first acts of Naturefriend activism.

Improving workers’ health and living conditions was seen by some as an end in itself, by others as a means to empower them for the wider class struggle. Even if opinions and ideologies were not necessarily uniform, the organization saw itself as part of the international socialist family, constituting the cultural pendant to party and union. Political activism was promoted within the TVdN. In some groups, like the Swiss national brand, being an ‘organized’ member of party or union was not a precondition for a Naturefriends membership, but unorganized members should explicitly be introduced into these organizations. Also, unorganized members could not be elected into offices, and members of bourgeois parties were seldomly granted membership in order to protect the TVdN against a ‘bourgeois infiltration’ (Schumacher, 2005).

The rise of the Naturefriends in the midst of troubled Times: a first Heyday

After the dark days of the First World War, people in Europe longed for nature and cultural exchange. Times were dominated by unemployment, austerity, homelessness – not necessarily good preconditions for a culturally coined Naturefriends organization of the working class. Yet, maybe these preconditions explain the success that would follow in the next years. By the time the first world war ended, the organization had spread significantly. Naturefriend groups could be found in Austria, Switzerland, Germany, France, Belgium, Hungary, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, the Czech Socialist Republic, Yugoslavia, Poland, and the USA (Zimmer, 1993). On an international level the TVdN soon turned into a melting pot for different societal and political groups, including conservative proponents of the living reform movement, party- or union-affiliated workers, socialists, communists, but also apolitical wanderers and naturists. This inclusive identity, as well as the wide range of offers for the whole family at reasonable prices (including hiking, climbing and mountaineering trips, basic accommodation in natural areas, photography courses and much more), all fueled by a neoromantic atmosphere of the postrevolutionary generation, led to a stark increase in members. As hinge between moderate reformists and the more revolutionary workers’ front, the TVdN experienced its heyday after the First World War as the ‘Green Reds’. By the early 1920s, the club had grown to more than 100,000 members, even though it was still far from being political mainstream (Hoffman, Zimmer, 1986).

A key to this success were the houses, which are still one of the most prominent element of Naturefriends’ work today. In a spirit of self-help Naturefriends themselves were involved in their construction and maintenance. This did not only bear impressive fruits with real material value, but also supported the identification of the individual with the organization. Further, this spirit, together with the idea of soft tourism and an alternative approach to sports helped to attract politically motivated and nature-romantic youngsters into the organization, and thereby into the environment of the workers movement. At last, the houses also supplied cheap accommodation and room for activities, becoming the basis for the Naturefriends’ way of ‘Social Hiking’.

On the left: Picture of Naturefriends house Brombacher Hütte built near Frankfurt 100 years ago (Foto: Götz). On the right: A group of 25 international volunteers renovated the hut in 2014 (Foto: IYNF)

The success of the TVdN influenced the typical composition of the majority of Naturefriends groups. While in early years women were drawn into the organization due to their personal connections rather than political ideology or special interest, the 1920s turned the TVdN into an organization dominated by families, with more and more women joining the club and taking up offices. Signature features became making music, especially playing the mandolin and singing in the group, as well as practicing photography (Schumacher, 2005). At the same time autonomist traits paved the way for the creation of youth sections, one of the first being the German Youth section under the leadership of Loni Burger.

With the beginning of the 1930s ‘mass tourism’ slowly became an issue to be dealt with. Increasingly workers in central Europe were granted holidays and the TVdN acted as their traveling agency. This way, the TVdN would address a wide range of people and bring them together on hikes, fostering a social exchange of different classes and camps. Those participants that could identify with the ideology would soon join the club. At the same an internal dispute came up: What about those that use TVdN offers as cheap holiday trips, but do not align themselves with the ideology of the TVdN? After all, this discussion points back to a conflict between idealistic and material values of TVdN activities, which would not be settled in a while. For now, a much bigger disaster than an internal dispute would unfold, destroying much of the progress made by the TVdN so far: the Second World War.

Youth Work within the early Naturefriends Movement: A Conflict between Generations

The youth had a special role in the TVdN at least since the introduction of the first program for child- and youth-work to the political agenda in 1908. It was declared that raising healthy, critically thinking members of the working class was not only a goal in itself, but a means to prepare for upcoming class struggles. Some members saw youth work within the Naturefriends movement as a counterbalance to the boy scout movement, which, according to Christian Blohm, member of the Naturefriends New York, was advertised as being apolitical but “clandestinely [integrated] children and youngsters in a nationalist and anti-labor agenda” (Gross, 2014). Youth work in the Naturefriends is supposed to aim at the opposite. As Loni Burger, head of the first German Youth segment of the Naturefriends puts it in 1926: “Being a Naturefriend means being a fighter for a better humanity, means to break with the traditions, means to give life new significance. Being a naturefriend means to be pioneer for the socialist society. For this, the old are mostly not capable, and the young generation has to be educated in this spirit. That is why the youth has to wander with us” (in: Hoffman and Zimmer, 1986, p. 30).

Image 4: A Naturefriends group from Pirna-Copitz (Saxony), on a hike with their mandolines around 1923 (in: Hoffman and Zimmer, 1986). .

The history of the Naturefriends movement was always coined by a certain tension between adults and youth. They increased significantly in the years before the Second World War, with more regional groups calling for independent youth segments like those being established in Germany. In 1926 the Naturfreundejugend Deutschlands (NFJD) became an official segment of the German Naturefriends, even if they remained dependent on the adult organization in all aspects. Yet, even in the short timespan until the ban of the TVdN in 1933 one can see a development towards more independence. While the official youth leader and half of the youth committee were elected by the adults in 1926, in 1930 the youth leader was already proposed by the youngsters and decided upon by the adults, and the whole committee was elected by the youth. This development was not welcomed by all members of the network. Some (older) members argued in a Marxist understanding that the youth should line up in the workers’ front and fight together with the adults for the liberation of the working class. In their understanding, independence of the youth would only be counterproductive as it divided the workers’ front. Contrary, most young Naturefriends stressed the need for independence in order to be able to address specific concerns of the youth and win more supporters. The struggle for independence would still last for almost half a century before the International Young Naturefriends would arise as independent branch of the Naturefriends International in 1975, and, as will be shown further down, even then the intergenerational conflict was far from being settled.

The rebellious feeling in those days peaked on the workers’ youth meetings of the 1920s and 1930s. Organized by Naturefriends groups in collaboration with other socialist organizations and labor unions, these gatherings turned into pilgrimages for the subcultures of the time. According to contemporary witnesses, these events were comparable to the rock festivals in the 60s and 70s, attracting many of the often unemployed youth from all over western Europe. The open approach towards naturalism and the free body culture arguably added to this spirit, and today we can only imagine what a blast these international events must have been – at times when globalization was still about to unleash its full scope.